Review: Jason Allen-Paisant - Thinking with Trees

Mon, Jun 26, 2023

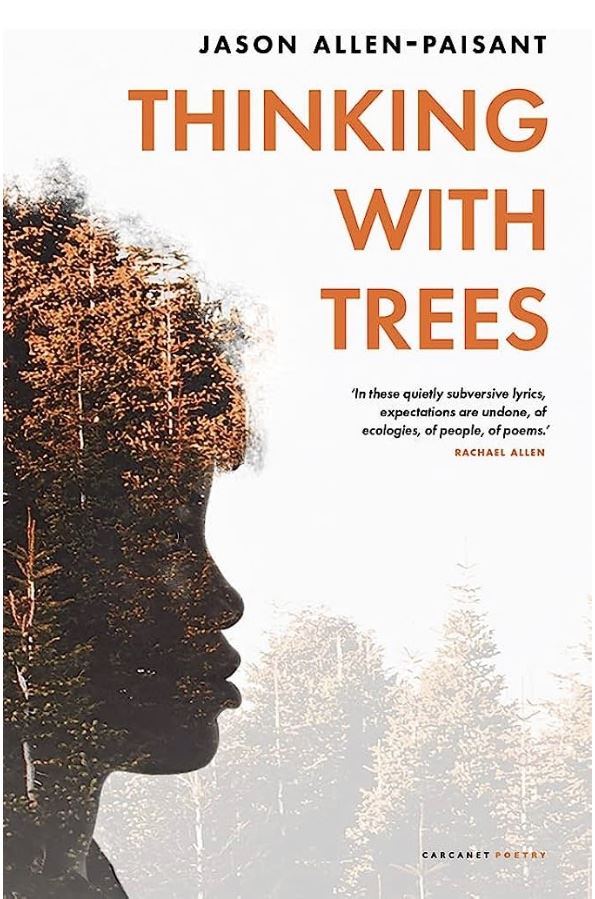

JASON ALLEN-PAISANT – THINKING WITH TREES – (CARCANET, £9.99, 2021)

A review by WORD!s Pam Thompson, originally published in Under the Radar (Nine Arches)

Roy Fisher once said of his home town, “Birmingham is what I think with”. Though not only an urban poet, Fisher’s poetic thought began with his home city. In his debut collection, Thinking With Trees, Jason Allen-Paisant’s poetic thought originates in Coffee Grove, the Jamaican village where he grew up, and where:

The woodland was there

not for living in going for walks

or thinking

Trees were answers to our needs

not objects of desire

woodfire

(‘Walking with the word ‘tree’)

Allen-Paisant’s thoughts oscillate between his experience of a rural community, where being on the land was associated with work, and walking in a suburban park. The poems are meditations on the idea of ‘leisure’: what it means and who has access to it. They interrogate a colonised past and the intersections of race and class, “To have money/ is to have time/ To have time is to have the forests/ and the trees” (‘Walking with the word tree’). The meditations take place in Roundhay Park, near Leeds, the city where the poet works as a university lecturer. He has money, he has time, and can experience something like solace and what seems like transcendence and oneness, “I am painted dancers sprouting// from the vines/ the strings of my body vibrate// to the strings of the rain “. (‘Among the great oaks in autumn’) In ‘Right now I’m standing’, the poet stops to examine a felled tree, “raspberries feed on its breath/ … beetles thrive in the slurry middle”. What follows sounds like, and is, a joyous exhortation:

Listen there is nothing as exhilarating

as the feeling of light coming into you

Yet in its wake:

Though people

look suspiciously

stand and listen do not go anywhere … //

we have been property

In that last line, Allen-Paisant references the poet Lucille Clifton, who said that when she tried to write nature poetry, there was always another poem underneath it because race was always present. For the poet standing in a suburban woodland “doing nothing” is a political act, “we have been the workers/ just the workers”. The Romanticism is necessarily skewed, and powerfully so, by reminders that taking up space and time in nature has not been possible for people of colour, and particularly Black people.

The park, for Allen-Paisant, is a bounded white-dominated space, as is nature writing within the Romantic tradition. Throughout, the poet interrogates and critiques the tradition and his uneasy place within it. ‘Daffodils (Speculation on Future Blackness)’ envisages a different type of reality for Wordsworth’s poem:

Imagine daffodils in a corner

of a sound system

in Clapham

Can’t you?

Well you must

try to imagine daffodils

in the hands of a black family

on a black wall

in spring

Just as in Wordsworth’s The Prelude, experiences of poet as boy and poet as man are overlaid. The layering for Allen-Paisant, is more complex, and insights behind it, both more interesting and disturbing.

The park is also an enclave for dog walkers. Dogs, off lead, run up to the poet, their owners, seemingly oblivious to any perceived threat. In colonial history dogs were trained by plantation owners to round up runaway Black slaves and to keep working slaves in check, “this mauling / of the Black body / the violence that made / White life possible”. (‘Essay on Dog Walking (II)). In ‘Masochism’ “a big strong dog terrorizes/ a gathering of black families/ celebrating in the park” the dog, Reggie, being allowed to create mayhem, whether knowingly by the owner or not, before it is called back. Though the speaker continues walking and the language appears Romantically lyrical, “ my heart falls back / to this joy of grass birds flowers”, disquiet is unavoidable due to feelings:

of past deep down

that knows the dog only

as an attacker

a marker of boundaries

Even though each poem in Thinking With Trees has a title, the decision to leave the poems unpunctuated (and knowing that the poet’s preferred process was writing while walking, either in notebook or on phone) gives the sense that the collection is one long poem. I am thinking more of American poet Jack Spicer’s idea of the serial poem than Wordsworth’s The Prelude. In a video promoting the collection, Jacob Allen-Paisant says he surprised himself in what emerged in his poem/essay, “this refusal of erasure”:

Let us think about

what it is to go walking

to be a body that walks

works here

(‘Essay on Dog-Walking (IV)’)

Pam Thompson is a writer and educator based in Leicester. Her publications include The Japan Quiz ( Redbeck Press, 2009) and Show Date and Time (Smith | Doorstop, 2006) and Strange Fashion( Pindrop Press, 2017). She is a 2019 Hawthornden Fellow.